I will admit that as I get older, Christmas gets harder. Not because I am inundated with things to get done and organize, shopping to do, events to plan, people to worry about, presents to agonize over, but rather the opposite: I find it harder to even care. Despite the unplaceable feeling of yearning and temporary homesickness I sometimes suffer from at this time of year (whose pangs can be quite sharp when they do hit me, thinking of family and friends back home), I feel, in many ways, that I have extricated myself from the whole process. Almost as if, being here in a far away, ‘foreign’ country for so long that celebrates Christmas in its own, peculiar and inimitable way (see my piece on Japanese Christmas for a more detailed critique), I have become able to see through the commercial hype and brain-clogging claptrap of it all the more clearly – the accumulation and repetition and the sheer predictability of it all just a fixed point on the calendar that we know will come around at precisely the same time each year and be celebrated in exactly the same kind of way.

Which is the whole point, I do realize. Societies and individuals need festivals and occasions to come together, a chance to celebrate something more than the focus on the self and ‘getting ahead’; to move out of our own self-obsessed spaces for a while and spend time with loved ones (despite the ridiculous amounts of stress that this seems to cause so many people!): wind down after a year of working and trying to just psychologically survive in this exhausting and overwhelming contemporary world, which, this year especially, has so depleted the energies and the spirits, leaving us feeling like broken and enervated husks. Traditions exist to allow us to strive for something higher, or at least more generalizingly human. Plus, they can be very enjoyable in the right circumstances and frame of mind: even joyful; something to look forward to and be excited about: that beautiful, piercing, reflective, melancholic end-of-yearness, when you look back and mull over what you have done and what you haven’t, coupled with the noise, and the smells, and the touching realities of the standard, complicated, family Christmas.

I think for me it all comes down to the loss of magic. And the terrible pressure I always feel to try and replicate it. Which is never going to be possible. Not ever – unless you yourself have children and can enter their pure and innocent world and believe again; or at least let their own beautiful unsullied enthusiasms rub off on you………perhaps then, and only then can you re-enter, to some extent, that frosty wintry wonderland of elves and reindeer and Silent Nights and holly and No Cribs For A Bed. Because, when Christmas was truly magical, you were a child and so believed in the lie of Father Christmas; that snow -whitest of lies (that I am very glad we were told because I have such intensely beautiful memories of that time), that to try and access them, now, in the face of the present, soul-clagging reality of department store Xmas and the same, tired old songs repeated year after year and the hideous poinsettias and discount tinsel and cheap, red felt Santa costumes and tins of solid jellied cranberries – it can, on occasion, leave a man feeling almost desolate.

We have tried. Over the years we have faithfully attempted to stir up some genuine Yuletide magic in our house here in Kamakura by setting up twinkling Christmas trees, putting up the fairy lights (which always slightly do the trick for me, I must say), and putting on the relevant music – right now as I write this I am listening to Japanese electronic pioneer Tomita’s Snowflakes Are Dancing – synthesizer reworkings of Debussy piano pieces that have the requisite sparkle and are giving me some vaguely Christmassy feelings in the pit of my stomach, but sometimes it can feel as though there were some kind of futility lurking beneath it all. Why do we keep doing it? We are not Christians (although I have some residual feelings myself in that regard) and here, in any case, it is usually just another day in the week and nobody else on the street is doing it and it can feel as if you are flaying yourself into trying to get that feeling back, that marvellousness of memory from when you were a kid that you know still lives within you somewhere, but that you know, in your heart, you never will.

No. The best recent Christmases (I never go back to England for it now – I prefer to return in the summer) have been the ones where we have just said f*** it, let’s just get away and do something different. Although I was neurotically worried that I would feel bereft and depressed just relinquishing Christmas and not going through the motions, in fact, the first time we tried doing something new, when we went down to Kyoto in the freezing cold weather a few years ago, it ironically ended up feeling more Christmassy in the end than anything we had done for many years through the sheer spontaneity of each day’s discoveries, the exquisite environment, and then happening, purely by chance on Christmas Day, to come across a Japanese restaurant by the Sumida river that was traditionally Nipponesque but which also had a small glowing Christmas tree in the corner that felt beautifully and unexpectedly right. In the same way, jetting off to Florida and New Orleans with Duncan’s family two years ago also shook things up in delightul ways: it was almost as if by nutcracking open that Fabergé egg of familiarity and repetition you could see the light again.

I know that perhaps the majority of people deep down really are sticklers for tradition and want to do things exactly the same way every year – I remember my mother trying once, in an attempt to do something a bit different for a change, to have Christmas dinner in the evening, by candlelight instead of at the required 3pm around the time of the Queen’s Speech, a break with tradition that I was completely for personally ( I get deeply bored myself by deadening routine and stultifying traditions that can brook no compromise), but this change of precious habit caused such consternation and mayhem and regret among everybody else present (somehow it apparently‘didn’t feel right’ for various reasons), that no changes, to my knowledge, were ever suggested again. Like me, then, I suppose my family are also chasing the ghosts of Christmas past and want, again, to enter that exhilaratingly enchanting and enchanted space where my siblings and I, as young children, would rush downstairs to the Christmas tree lights and decorations to open our huge bags of presents, utterly convinced that Santa Claus and his helpers had really been there, excited to the point of delirium, and overjoyed that this nebulous, external presence who had drunk his glass of sherry and eaten his frosted biscuits and flown on a sleigh ride in the starry skies of constellations had somehow managed to brush our living space – and are trying, through ritual and renactment, to bring it all back again, to now.

But this is all something that I can’t, and don’t want to, try to go back to any more. Duncan and I don’t even usually give each other presents (something I feel rather conflicted and guilty about: recently my family in England and I also decided that it was just too much bother buying and packaging and sending things from our two, very distant countries; part of me does just feel it is an encumbrance, but at the same time, I feel childishly jealous and regretful in a way) – but on that vividly memorable trip to Kyoto, the first time we had ever truly broken free from the Christmas traditions, we just decided that if we saw something small that we liked, we would buy it for each other. In the end, that was what we did: just a nice winter scarf each – but somehow it felt better, more precious, and more suited to the original Christmas spirit, than this excess of requested gifts that cost the earth, which, although in some ways expressing love, do in other ways to me seem the antithesis of the original Christmas.

We would always have a Nativity play in my primary school every year, little children dressed up in the familiar Bethlehem roles, a reimagining of time and place that always took me close to the more transcendent aspect of Christmas (particularly the music: I always have been a total dreamer and wanted to escape from reality), as well as sometimes going to the local church not far from our house for a ‘Christingle’ celebration on Christmas Eve that saw children dressed in white and red ceremonial garb carrying foil-wrapped oranges with candles in them down the darkened church aisles. That vision, and the smell of the church, and the heartwarming singing of carols, was always the perfect start to Christmas Eve for me, the contrast between otherwordly solemnity and then the more animal-like familiarity of our house on Dovehouse Lane where we would then come home and eat practically a whole giant tin of Cadbury’s Roses chocolates under the glimmer of Christmas lights, a selection box of caramels and nuts and fruit filled chocolates that we had every year, a Chapman tradition, and which we would stuff our faces with in anticipation of the glorious feast that would be Christmas dinner the next day. I suppose these are the smells now – the loitering smoke of frankincense and the eerie, and absorbing, smell of churches; oranges, and spice, and the gorgeously evocative scent of Christmas trees themselves, pine needles coating the living room carpet to the exasperation of my mum who was always having to then vacuum them up (in my memory we always had real trees – plastic ones just aren’t the same), that most evoke in that ghostly, emotionally overwhelming sense we call smell, the magic that I sometimes just can’t help, now that I am much older, and in spite of myself, still trying to chase.

This year, though, forget trying to reawaken English dreams of snowmen and walks under Yew trees and clear, starry skies (though the moon has been very beautiful here recently). I have been, like so many of you I am also assuming, just so exhausted by the events of the world and the horrors of this year, not to mention the strains of my job and various health issues that have meant administrative and financial hell here in the world of Japanese hospitals (and a sense, at times, that my life is not entirely my own), that I just don’t have the capacity to try and contrive any heart-searing, emotional replicas of Noël. We are having no tree this year.

*

But despite all of the above, now that my Christmas and New Year holidays have begun, and I have retreated into my much needed slob of a cocoon (no one reading this has any idea of how truly lazy I am), after a week, since finishing work, of socializing with Japanese friends that I wouldn’t get the chance ordinarily to see, of cooking while listening to my favourite records in the kitchen (heaven), and some days just doing nothing, or else going out to the cinema by myself or with Duncan, I have had the luxury ( and I realize how lucky I am in these days in Japan of death from overwork and exploitation and wars and death in Syria and elsewhere and everything else to even have this time, this life; most of my Japanese colleagues don’t); the true luxury of beginning to feel a sense of life and possibility coming back to me, an untightening of some of the stress, and a sensation that my heart and mind and senses are open again to whatever is coming next.

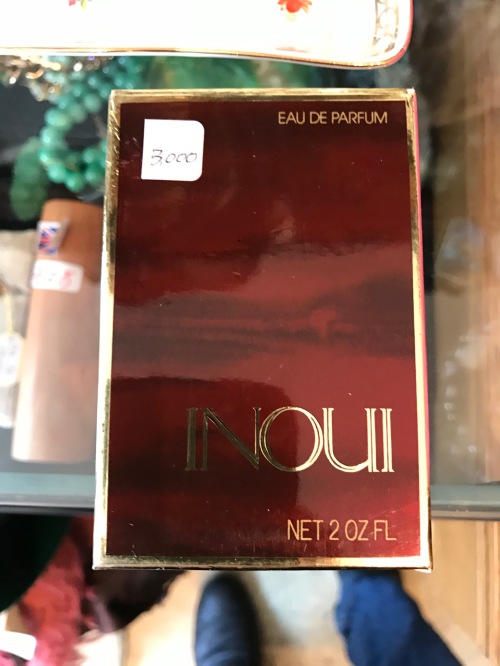

Which, right now, just seven days from now, is Christmas. And you know what, this year I think I am fine with just being here in Kamakura and going off to Tokyo and Yokohama for days out and not bothering with too much Christmas fuss (though I have considered cooking my first ever Christmas dinner, or else, if we can’t bothered, we might go off instead to a theatre restaurant we like in Ueno where we once saw the Bolshoi perform Swan Lake and I cried like a baby). Tokyo, like most cities the world over, is of course in ‘festive mood’ at present, and when I went off to Shinjuku on Friday to see a film and do some perfuming, I caught a glimpse, despite myself, in the cold, lung-freshing air and the lights and the shining department store baubles, of something that felt a little bit like Christmas. I also was on the hunt for a perfume that might do the same, and was thinking that Rêve D’Ossian, a curious perfume I had smelled before but not properly tried on my skin, by revived nineteenth and early twentieth century Oriza L LeGrand, might do the trick.

I adore frankincense. I find it such a beautifully luminiscent, soothing but simultaneously spectral smell, and am rarely without the essential oil, which I use in the bath, in face creams, on the chest when we have colds, or even a drop on the tongue at night to help me sleep. There are some natural essences that you are inherently ‘at one’ with, and frankincense, like bergamot, sweet marjoram, clove and patchouli, is that for me. In perfumery, though, I rarely find a frankincense that truly works. They are usually clad in far too many harsh, aggressive, ‘incense’ and synthetic wood accords that are supposed, I think, to make you think of Bedouin fires in the desert, Omar Sharif, or the Three Wise Men (even Comme Des Garçons brilliantly holographic Catholic cathedral Avignon eventually, unfortunately takes this path): but to me, while obviously seductive, mysterious, and erotic, these incense perfumes don’t reveal the true, apparitional ethereality of frankincense, which, as humans have known since ancient times, really is a communion between this world and the next.

Shinjuku Isetan, probably Tokyo’s best department store for niche perfumery, has a selection of Oriza L LeGrand fragrances, though most of them were behind the counter when I went and I had to ask specifically to be able to sample them (perhaps they are just a touch too old fashioned for trendy, Tokyoite contempories). Relique D’Amour, for instance, one of two frankincense perfumes by this house, is not only ‘old’, it smells positively ancient. Beyond the grave ancient; creepy, like a damp crypt in a French monastery collecting water. Quite fascinating, actually, and definitely one for the pondering gothic and morbid among us, with its notes of greenery (the moss and the ivy creeping on the walls outside); of rising damp; waxed wood (the pews in the church that stands above) and the light, dewy breath of fresh lilies as you first enter the sacristy. Christmassy, perhaps, but only for true Brides Of Christ and other adherents of the devout. You can practically feel the cold, inspiriting breath of the Holy Ghost.

Far more evocative of my personal childhood Christingle memories, and a much more soothing, benevolent perfume in general, is Rêve D’Ossian, a true frankincense scent that achieves a beautiful balance between cold and warmth. Apparently originally released in 1905 but reorchestrated for 2012, in some ways this is like the frankincense equivalent of Serge Lutens’ La Myrrhe of 1995: aldehydes lifting the mystical incense to fresher heights and throw, while a bed of labdanum, benzoin, musk and sandalwood/vetiver lie beneath faint gestures of pine trees and cinnamon. The effect is cogent and natural – like the cordiality of bodies congregated in a Christmas Eve church service; the lingering warmth of incense huddled in the rafters; a semi-religious gentleness and aerated smoothness that took me out of my immediate environment (Shinjuku station is the busiest in the entire world, as, probably, are the streets) and which put me, for a moment or two at least, in a definitively different, more contemplative, and Christmas-like, space.